Cross-border maize trade (2013 - 2014)

Last update: 24 February 2023

This project was funded by the Agricultural Learning Network for the Uplands (AgriNet), under the Northern Uplands Development Program co-financed by the European Union and by the French, Swiss and German cooperation agencies.

- Duration: 2013 - 2014

- Study site: Laos

- Background& Introduction

The Northern Uplands are among the poorest regions of Laos, but these regions are also quickly opening up to change under the impulse of regional integration policies (Greater Mekong Subregion, AEC) and dynamic neighboring markets (Vietnam, China, Thailand) hungry for agricultural commodities. Regional markets offer opportunities for smallholders to increase and diversify their incomes (e.g. through the sales of agricultural products such as maize, soybean, sesame, mung beans, tea, medicinal plants, bamboo, etc.). Regional markets also bring a risk of increased farmer vulnerability and exacerbated inequalities.

Research objectives

- Main Objectives : to study patterns and outcomes of regionalvalue chain(s) for maize in HP; to identify opportunities for a betterinclusion of smallholder maize farmers (female) into regional value chains formaize in HP.

- Specific objectives

:

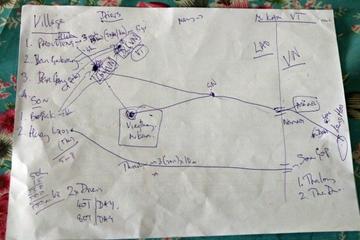

- to map theregional value chain(s) for maize in Huaphanh;

- to identifyconstraints to the inclusion of smallholder farmers in maize value chain(s);

- to informstakeholders about regional market opportunities and upgrading opportunities;

- to helppolicy makers make regional maize value chains more efficient, fair andinclusive.

Findings

Maize trade

- Cross-border maize value chains were short (cf.distance covered and number of stakeholders involved) and simple (little to noprocessing).

- Opaque procedures currently in place to granttrader access to maize producing villages create maize territories in which thetraders’ rules of the game are unchallenged.

- Contracts. Were signed by the trader, the village head(on behalf of the farmers) and the District Agriculture and Forestry Office.Traders provided maize seeds at a slightly lower price than market price oncredit; gave planting advice (the first years); and build roads to access themaize fields. Village heads signed the contract, facilitated communicationbetween farmers and trader, collected the maize and distributed seeds. Districtauthorities established the season’s minimum price, signed the MoU with thetraders allowing them to do business and checked the seeds.

- Distributionof value. Farmers captured 83% of total profits (68% if the labor costs wereincluded). Their average annual income was 612 USD/ha (annual profit: 320USD/ha). Collectors captured 6-10%of total profits, which was explained by their low scale of operation, and bythe fact that local collectors were merely hired by larger traders to transportmaize over short distances on very poor roads. Traders/exporters captured 10-21% of total profits, thanks toeconomies of scale and scope (allowed by the combination of maize trade withthe trade of other commodities and with road construction activities), andbecause they were able to carry out value adding activities (e.g., drying). Transportation costs(fuel consumption, vehicle failures) represented on average 17% of the costs ofthese traders.

Mainissues

- Environmentaldegradation. Maize farmingcontributes to rapid soil depletion, deforestation and loss of biodiversity. Feederroads help intensify the rush to new land as fertility drops.

- Powerimbalances. Between traderswith access to uncontested maize territories secured through contracts and roadconstruction “agreements” signed with the complicity of district authorities;and farmers with limited resources, access to markets, market information,technical advice & extension, information about the contract, low storagecapacity, few alternatives (no local maize processing activities), and nofarmer organizations.

- Maizeterritories. The feeder road cum contract system described here enablesfarmers to access markets and to improve their livelihoods. While traders cannotbuild roads and tracks for free, and are entitled to benefit from theirinvestment, the creation of genuine maize territories over which the rules of traders(in a position of oligopsony) are uncontested is not acceptable.

- Priorityareas of intervention tolink maize farmers to cross-border markets in a more sustainable and fair way. 1/empower farmers (e.g., by creatingfarmer groups, setting up market information systems); 2/ eliminate entrybarriers to collection and trade activities and end the system of territories;3/ monitor contracts and improve contract enforcement; 4/ improvefarmer/collector access to credit and to post-harvest technologies; 5/ Helpsmallholders diversify livelihoods away from maize; 6/ ease trade by improvingtransportation infrastructure and by making the export permit system lessburdensome.

Nam Meo border crossing

Nam Meo border crossing

Maize feeder roads

Last update: 24 February 2023